Jobs Interest In Design

Jobs’ plan to make industrial design the centerpiece of Apple’s comeback should have been no surprise. Design had always been central to Jobs’ MO. Unlike Jony, Jobs didn’t have a formal design training, but he had an intuitive design sense that went all the way back to his childhood. He grew up in a house that was inspired by the tract homes of Joseph Eichler, a post-war developer who brought the Mid-Century Modern aesthetic to the architectural landscape of California. Although Jobs’s childhood home was what he would have probably referred to as a knock-off of an Eichler (what Eichler fans call a “Likeler”) it made an impression on him. Describing his childhood home, Jobs said, “I love it when you can bring really great design and simple capability to something that doesn’t cost much. It was the original vision for Apple.”

In fact, Jobs’s appreciation for good design may well have run in the family. “I thought my dad’s sense of design was pretty good,” Jobs said, “because he knew how to build anything. If we needed a cabinet, he would build it. When he built our fence, he gave me a hammer so I could work with him.”

One concept that stuck with young Steve while he was working with his father was that good design wasn’t just on the exterior of an object. It permeated. “He loved doing things right. He even cared about the look of the parts you couldn’t see,” Jobs recalled. He said that his father refused to use poor wood for the back of cabinets, or to build a fence that wasn’t constructed as well on the back side as it was the front. Jobs likened it to using a piece of plywood on the back of a beautiful chest of drawers. “For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.” Jony also shared this sense of quality. He’d never slap a piece of cheap plywood on the back of his products.

For Jobs, design was not how an object appeared, but how it worked. ”Most people make the mistake of thinking design is what it looks like,” Jobs famously said. ”People think it’s this veneer — that the designers are handed this box and told, ‘Make it look good!’ That’s not what we think design is. It’s not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.”

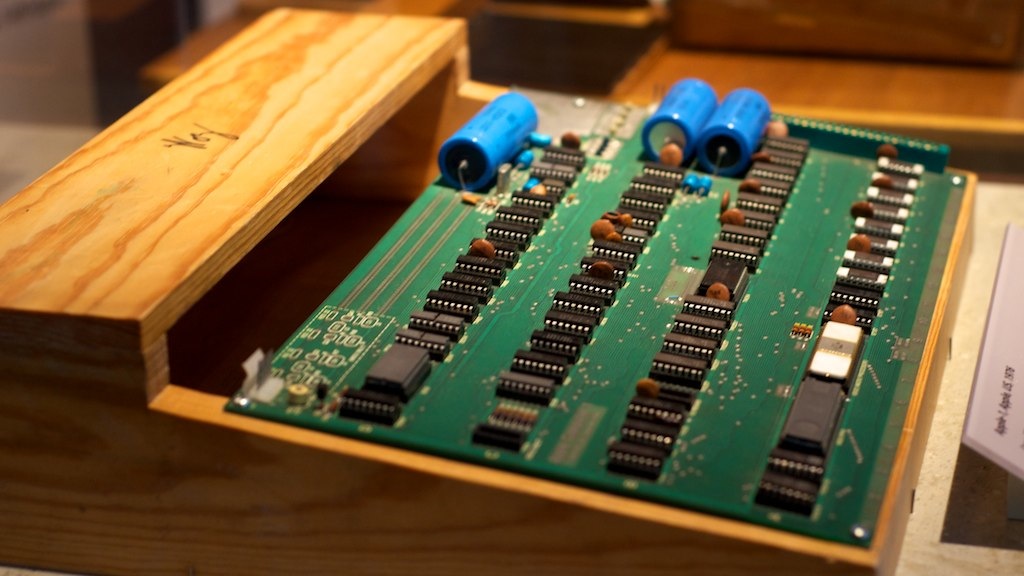

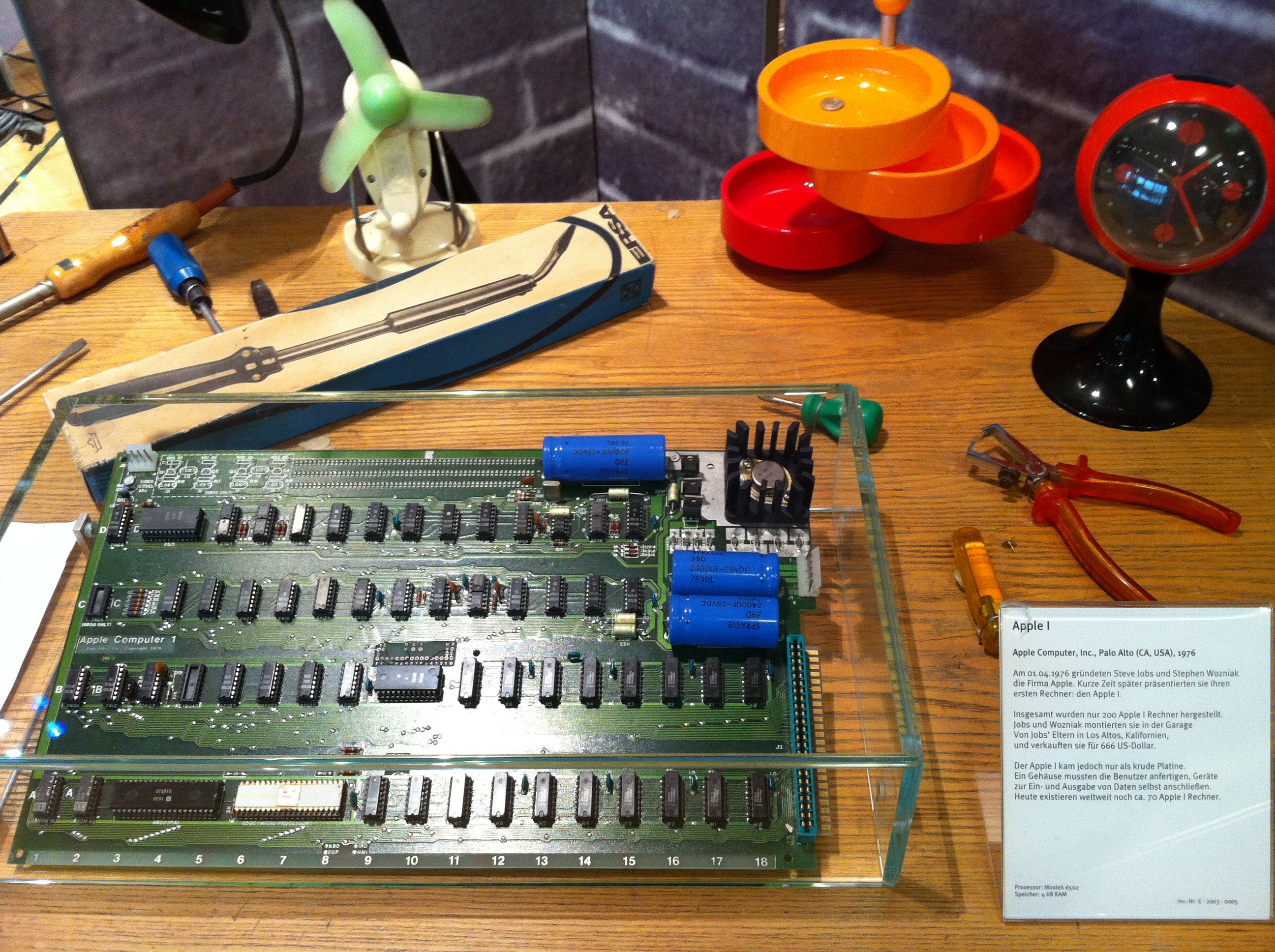

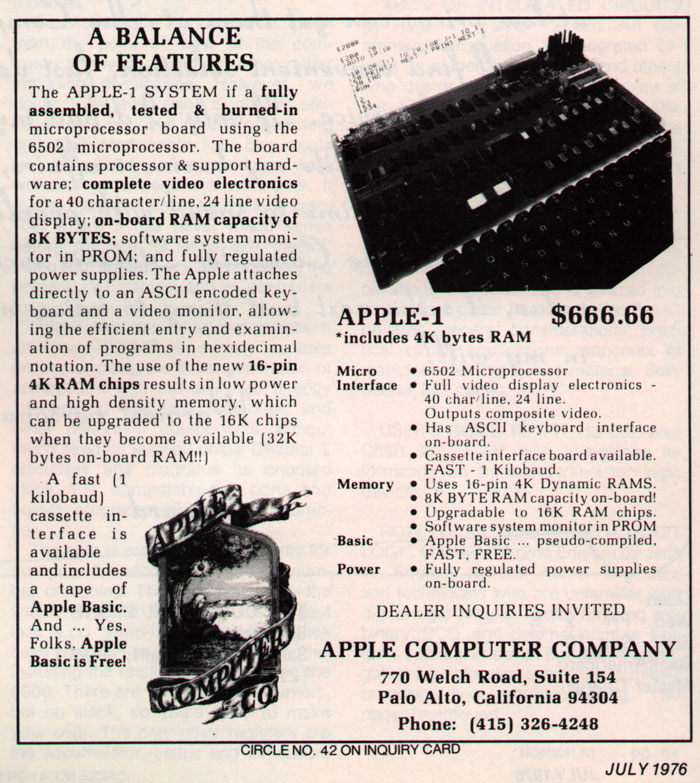

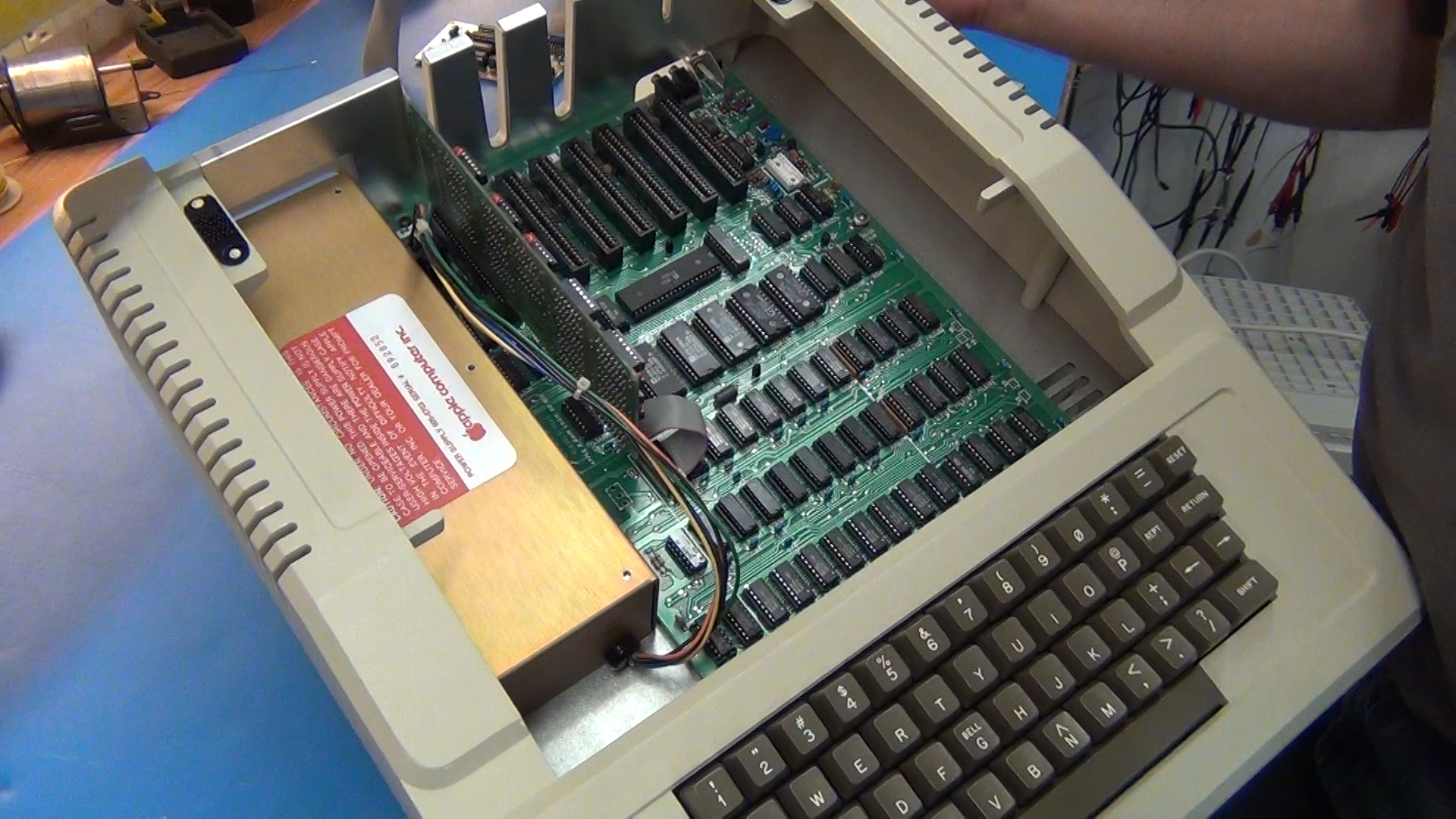

This sense of design would eventually make Jony’s design group the very heart of Apple. But it is a sophisticated definition of design that took Jobs some years to arrive at. At first, Jobs was more concerned about appearance. When Steve Jobs helped create one of the world’s first personal computers, the Apple I, back in 1976, the hobbyist aesthetic of the early PC scene offended him. It was too DIY. Designed by his friend Steve Wozniak and assembled by hand in a garage, the Apple 1 was just a motherboard, which customers would build by supplying their own power supply and monitor, then putting it in a “case”, which was usually an old orange crate.

This was not the way Jobs wanted it. He wanted to transform home computing from a DIY affair into a real industry. Jobs wanted Apple to sell finished computers to paying customers. He envisioned the PC as something that you took home and plugged in, like a TV or a toaster. That meant that Apple’s computers needed to look like real products with cases that signaled their function as consumer products, no assembly required. It had to have a nice plastic case with gently rounded corners and a warm, welcoming texture. A well-designed exterior would inspire first-time computer buyers to take the plunge, making it appear to be no taxing to use than any kitchen appliance. You just unboxed it and plugged it in.

Thus was born the Apple II, which first came off the drawing board in 1976, soon after Jobs and Woz sold the first batch of Apple Is. It was the computer that would change Apple’s fortunes, and while Wozniak concentrated on getting the cutting-edge hardware right, Jobs focused on what he thought really mattered: the way it looked. “It was clear to me that for every hardware hobbyist who wanted to assemble his own computer, there were a thousand people who couldn’t do that but wanted to mess around with programming… just like I did when I was 10. My dream for the Apple II was to sell the first real packaged computer… I got a bug up my rear that I wanted the computer in a plastic case.”

Other companies were putting PCs in cases made of sheet metal. They were cheap, and offered great electromagnetic shielding, but they looked utilitarian. No one had ever even thought to treat a home computer like an appliance and put the guts of it in a plastic case. That fact alone created a problem of precedent for Jobs: even he had no idea what a finished computer should look like.

To gather inspiration, Jobs scouted department stores. He finally found what he was looking for while strolling the kitchen section at Macy’s and coming across a counter full of Cuisinart food processors. It was perfect. Like a Cuisinart, a computer was made up of a lot of parts that were dangerous to the touch and intricately interconnected, but this complexity was hidden away beneath a nice molded plastic case with smooth edges, muted colors and a lightly textured surface. This was what Jobs wanted for the Apple II.

Initially, Jobs approached a couple of Silicon Valley’s top design firms, but he had a hard time getting them to take him seriously. He looked like a hippy and had no cash. He offered one firm stock in Apple. They declined (and deeply regretted it later). Eventually, however, Jobs was referred to Jerry Manock, a designer who had just left Hewlett-Packard and gone freelance. “When Steve asked me to design the case for the Apple II, it didn’t occur to me to say no,” he said. “But I did ask to be paid in advance.”

The case Manock built for Jobs was the first of its kind and a classic to this day. The primary goal was something that could be quickly and cheaply made. Jobs wanted to launch the Apple II at the world’s first conference for personal computers: the West Coast Computer Faire in April 1977, which was only a few weeks away. The size and shape of Manock’s case was determined by Wozniak’s motherboard. He gave it a sloping wedge at the front to fit the Apple II’s built in keyboard. It was also taller at the back to accommodate the Apple II’s expansion slots. Jobs — thinking, perhaps, of his father’s backyard fence — wanted the insides to look good if the user was to open the case, so he asked Manock to coat the cases inside with chrome. Manock ignored him, and Jobs never pursued the idea.

He was right not to push it. When Apple got the first molds of the new case back, he already had his hands full. They were in rough shape. They had to be filled and painted to look presentable, and the lids had to be sanded to fit their bases. Chrome inside would have just been another complication which Apple could ill-afford: the Apple II’s big debut at West Coast Computer Faire was coming up.

Manock had 20 cases made for the Computer Faire, but only three were working models with circuit boards inside. Jobs put the three working machines at the front of the booth to show to customers. He carefully stacked the seventeen empty cases at the back, making it look like they already had a production line going. His little subterfuge worked. Apple looked far more professional than other companies at the Faire. “Compared to the primitive stuff on view elsewhere at the Faire, our finished plastic blew everyone away,” recalled Manock. “Even though Apple was only a few months old, the plastic cases made it look we had already achieved high-volume production.”

As Jobs had surmised, it was the case that made all the difference. Before Bill Hewlett designed the first “pocket” calculator, most calculators were large, expensive, desktop models. HP expected to sell maybe 50,000 units. But Hewlett instinctively felt that scientists and engineers would love a small, pocketable calculator in a slim plastic case. He was right. HP sold fifty thousand of the iconic HP-35 calculators in the first few months.

The same was true with the packaging for the Apple II. A friendly plastic case had been all that was needed to transform it in the minds of consumers from a build-it-yourself project for geeky hobbyists into a plug-and-play appliance for the average customer. The Apple II wasn’t made for the kind of hobbyists who felt most at home soldering a circuit board: it was for people who wanted to run some easy-to-use software.

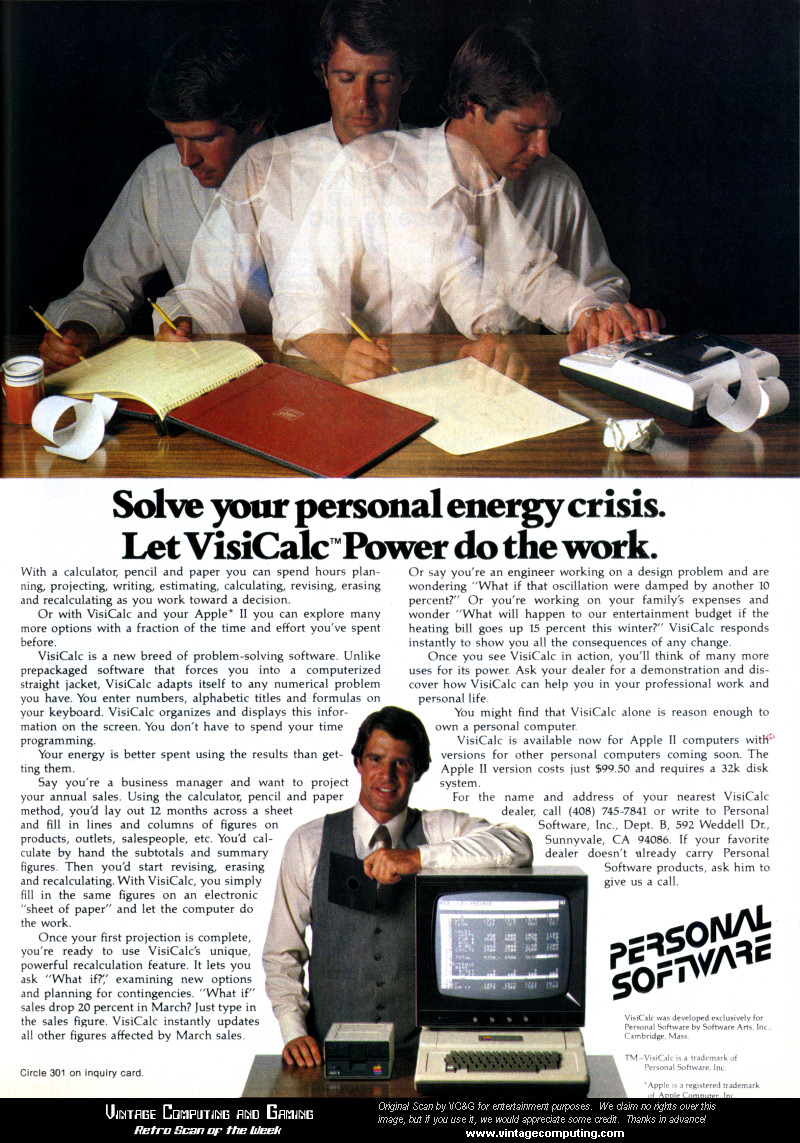

Soon, software for the Apple II started taking off. A couple of students from Harvard created the first killer app for the Apple II: Visicalc, the world’s first computer spreadsheet that allowed tedious business calculations to be made more easily. A killer app is a piece of software that drives hardware sales, like the Halo game on Microsoft’s Xbox: Customers by the hardware to run the software. More than anything else, Visicalc helped cement the Apple II as a must-have tool in most businesses.

Thanks largely to VisiCalc — the Apple II’s crucial “killer app” — the Apple II exploded tenfold in the first year, from $770,000 in 1977 to $7.9 million in 1978. By 1979, sales of the Apple II reached $49 million. It was the fastest-selling computer ever up until that time. Apple was only three years old and was already in the Fortune 100.

The Apple II’s case was just the beginning. Now that it was a success, Jobs wanted to get serious about industrial design, which he believed could be a key differentiator between Apple’s consumer-friendly, works-right-out-of the box philosophy and the bare bones, utilitarian packaging of early rivals like International Business Machines. “IBM has it all wrong,” he would say. “They sell personal computers as data-processing machines, not as tools for individuals.” Jony had the same instincts. At Tangerine, he hated the geeky aesthetic of 80’s electronics. They were designed only to appeal to geeks, not the much bigger market of ordinary people.

In 1981, with the PC revolution not yet five years old, Jobs thought Silicon Valley had just scratched the surface. Only 3% of US households had a personal computer (including toy systems like the Commodores and Ataris). Only 6% of of Americans had even encountered a PC at home or work. Jobs thought the home presented a huge opportunity. Trouble was, early computers weren’t easy to use. They required some knowledge of programming. Users had to type arcane commands into the so-called command-line interface.

It would take him five years, but the product Jobs envisioned that would represent the first truly uncompromised look at Jobs’ ideas about design would eventually arrive. It would be called the Macintosh.

Courtesy DigiBarn: http://www.digibarn.com/collections/screenshots/xerox-star-8010/

Courtesy DigiBarn: http://www.digibarn.com/collections/screenshots/xerox-star-8010/

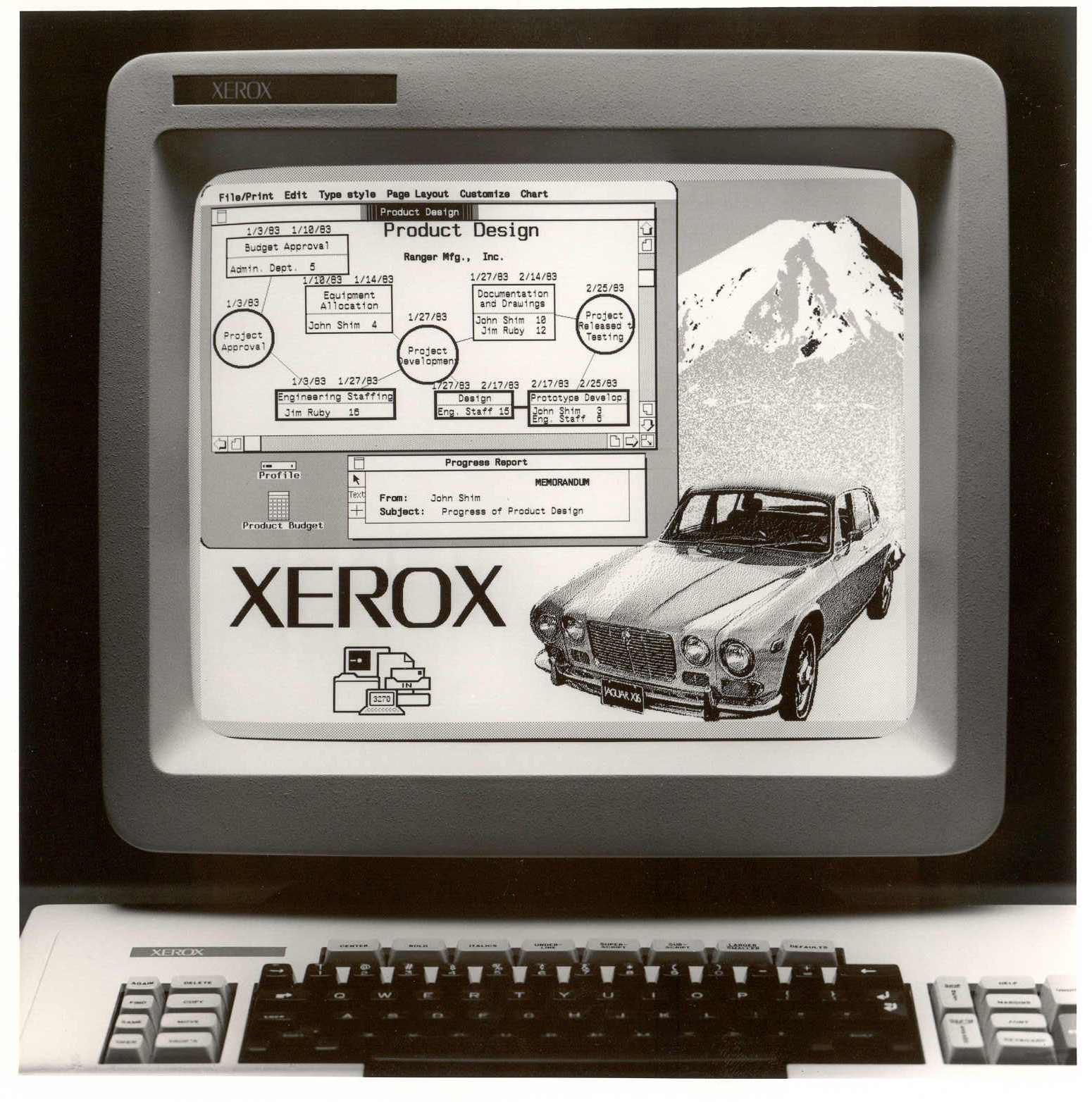

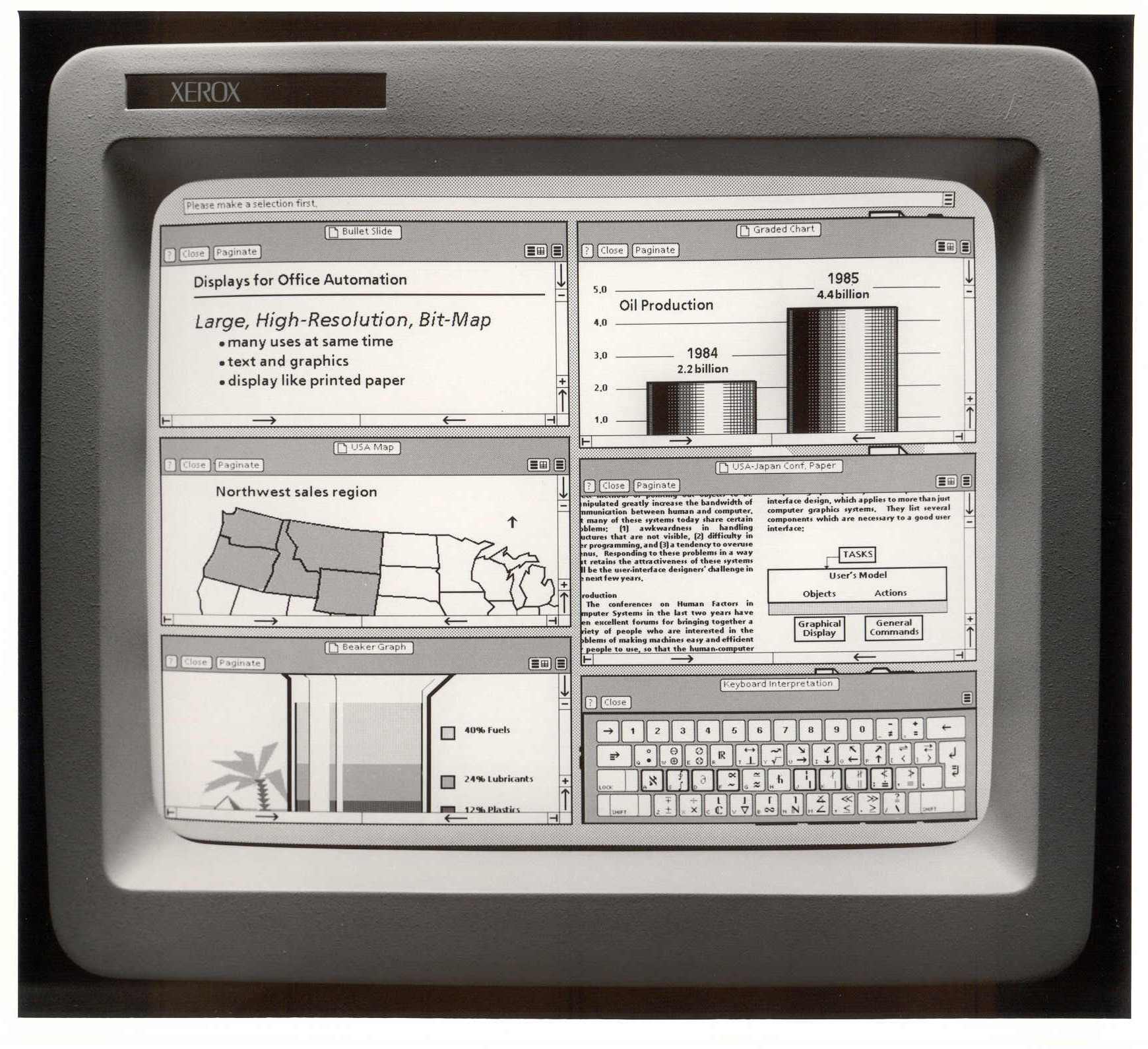

After getting a peek at the first graphical user interface in 1979 at Xerox’s famous research center, Xerox Parc, Jobs realized that a graphical interface would do for computing what Ford’s Model T did for the automobile — revolutionize everything. Jobs started calling the Mac the “first crankless computer.”

Key to making the crankless computer appeal to the masses would be to make it unintimidating, even “friendly.” But what does that mean? What are the physical attributes of a “friendly” product? This is something Jobs would discover through a prototyping process that designers like Jony were taught in Design 101, but Jobs discovered himself, intuitively.

Working with Manock again, Jobs had just three initial design constraints. To keep it cheap and make it easy to manufacture, Jobs insisted on one configuration and one configuration only; just like his hero Henry Ford’s Model T, which was available in any color as long as it was black. It would be ‘crankless.” Jobs wanted the Mac to be immediately accessible to anyone who sat in front of it, whether they’d laid eyes on a computer before or not. A new owner should just be able to plug a Macintosh into the wall, just like a Cuisinart, and press a button, and it would work. That meant no setup. It would have none of the wires and plugs of other PCs. It would be the world’s first all-in-one PC: the screen, disk drives and circuitry all be housed in the same case, with a detachable keyboard and mouse that plugged in the back. This was a new idea. In addition, the Macintosh needed to be small and not take up too much space on a desk, so Jobs and his design team decided it should have an unusual vertical orientation. This put the disk drive below the monitor, instead of to the side like other machines at the time.

Manock and his fellow designer Terry Oyama created numerous front and side view drawings showing how the disk drive slot looked with the CRT screen. Jobs reviewed the initial designs, pointing out what he liked and what he didn’t. “We explained why we were presenting certain forms, and Steve would comment on whether he thought they achieved their stated goal,” Manock remembered. Manock said Jobs often asked for three alternative solutions to a problem — something that would occur again and again throughout his career, especially when working with designers.

Jobs had a reputation as a volatile taskmaster, but Manock said he was positive and helpful. There were no tantrums. In fact, Jobs was always positive, Manock said. He never said he disliked something. Instead, he would say he liked a feature, but he liked another approach better. The models would be reviewed by Steve in a “like-like better” fashion,” said Manock. “I don’t remember any harsh rhetoric,” he said.

Manock and Oyama made a model out of white Foam Core, a rapid prototyping material that is easily shaped. Foam core models bring drawings alive, making it easy to see if a certain shape works instead of trying to imagine it. Jobs gathered the Macintosh development team together to critique it. Andy Hertzfeld, a key member of the team who wrote a lot of the system software, thought it was cute and attractive, and had a distinct personality. But Jobs knew how to critique it very precisely.

“Steve cut loose with a torrent of merciless criticism. ‘It’s way too boxy, it’s got to be more curvaceous. The radius of the first chamfer needs to be bigger, and I don’t like the size of the bezel. But it’s a start.’” Hertzfeld wrote. “I didn’t even know what a chamfer was…”

The design process continued for several months. Manock and Oyama made several new models, and Jobs assembled the team for their feedback. Every time there was a new model, all the old ones were lined up next to it for comparison. “By the fourth model, I could barely distinguish it from the third one, but Steve was always critical and decisive, saying he loved or hated a detail that I could barely perceive,” Hertzfeld recalled. It took several prototypes to finally get it right. Oyama also did some studies of the case’s details using an oil-based clay — the same clay used by designers in the automobile industry.

The first case prototype was machined out of clear Plexi-Glas, which took about a month. “By holding a stick of incense next to the lower air vents, we could see the convective air flow out the top vents,” said Manock. “This is how we came to add vents on the top surfaces… the smaller vents at a 45 degree angle on the back didn’t allow fast enough air velocity. Then Plastic Tooling Aids, near Boulder, Colorado did aluminum ‘soft tooling’ to give us production quality ABS plastic parts. These tools (molds) could be changed relatively easily as compared to the hardened steel tools that were capable of making 1,000,000 parts. I think we changed the disk drive slot at the soft tooling stage. When we were relatively sure of the design, the go ahead was given to start making the steel “hard” tool, which would take at least 3-4 months.”

When the molds were done, Jobs had 35 key members of the team celebrate their accomplishment by breaking open some champagne and “signing” the inside of the case.

To make the case durable and scratch resistant, Manock used the same grade of tough ABS plastic that was used to make LEGO bricks and gave it a fine, scratch-resistant texture. Troubled by the way earlier Apple IIs had turned orange in sunlight over time, Manock decided to make the Macintosh beige… starting a trend in computers that would last twenty years, and that Jobs and Jony would have to team up to abolish with the colorful 1998 iMac.

Like Jony, Jobs paid close attention to every detail. Even the mouse was designed to reflect the shape of the computer: it has the same dimensions, and its single square button corresponds to the shape and placement of the screen. The power switch was put around the back to stop it being switched off accidentally (especially by curious kids) and Manock thoughtfully put a smooth area around it to make it easier to find by touch. “That’s the kind of detail that turns an ordinary product into an artifact,” Manock said. It was exactly the kind of detail Jony paid attention to, adding a fiddle button to a pen or making the Newton’s lid pop like a car trunk.

The Macintosh looked like a face, with a slot for the disk drive resembling a mouth and the keyboard recess at the bottom looking like a chin. Jobs loved it. This is what it took to make the Macintosh look “friendly” — an anthropomorphic smiley face. “Even though Steve didn’t draw any of the lines, his ideas and inspiration made the design what it is,” Oyama said later: “To be honest, we didn’t know what it meant for a computer to be ‘friendly’ until Steve told us.”

Making the Mac friendly would be one of the keys to its success, and to the success of later products. Friendliness became a defining characteristic of Jobs’ intuitive design sense, and Jony’s too. Subsequent hit products like the iMac had a distinct, anthropomorphic personality and were manifestly ‘friendly.” While products like the iPod and iPhone were less overtly friendly, they are certainly approachable.

While Jobs had obsessed about the design of the Macintosh’s case, he had made some bad decisions about its internals. When the Macintosh was released in January, 1984, it only had 128K of memory. It was a choice Jobs had made to save money, but it was a fraction of what the Macintosh needed, making simple tasks like copying files grueling affairs. “What I (and I think everybody else who bought the machine in the early days) fell in love with was not the machine itself, which was ridiculously slow and underpowered, but a romantic idea of the machine,” wrote the science fiction writer Douglas Adams, an early fan.

Luckily, one of Jobs’s hardware engineers, Burrell Smith, had anticipated the problem. Forbidden by Jobs to even consider putting more memory in the machine, Smith had secretly included the ability for the Macintosh’s memory to be expanded to 512K. Apple was able to correct their mistake by releasing a much-improved 512K Mac just a few months later. Jobs would make a similar mistake with the first iMac a dozen years later; a mistake that ultimately made him work much more closely with Jony.

Unfortunately, the Macintosh was the last product that Steve Jobs would see to market during his first tenure at Apple. About 18 months after launching the Mac, in September, 1985, Steve Jobs lost a boardroom power struggle with John Sculley for control of Apple. Jobs was quit/fired by Sculley, an ex-Pepsi-Cola marketing executive that Jobs had recruited himself to be the company’s new CEO.

Even so, Jobs influence had such a strong influence on Apple’s standard for design, that his ideas persisted almost as long as it took him to come back to the company in 1997.

Snow White

While Manock and Oyama were working on the Mac, Jobs had also been searching for a design language for the entire company. Part of the genius of the Mac is the consistency its software. All the software that runs on a Macintosh confirms to the same standard rules, which makes it easy for users to understand and use. Menus and dialog boxes all looked the same, even between different applications. The file menu is always in the same place. Folders look and behave the same, and dialog boxes were consistent and predictable.

But while the software had a consistent “design language,” Apple’s hardware was all over the place. The company’s different divisions — the Apple II division, the Mac division, Lisa, peripherals — were all using different designers with different ideas. Apple’s products looked like they came from four different companies, not one. It drove Jobs crazy. Later, when Jobs returned to the company, he and Jony would establish a very clear design language for the company that went through several iterations.

Another factor was money. Both Apple and Jobs were flush with cash. As Jobs’ personal stake in the company approached $250 million, he traded in his tatty shorts and flipflops for expensive suits and tailored shirts. He began exercising his passion for art, architecture and design in Apple’s headquarters, which had to be gutted and refurbished with no expense spared, even if the buildings were brand new. Likewise, he insisted Apple’s ads, brochures and marketing materials were of the highest quality and of the highest aesthetically standard.

As far as Jobs was concerned, Apple had invested in the best programmers, the best engineers, the best accountants, but it hadn’t hired the best designers. Jobs started talking about making Apple in the 80s what Italy’s Olivetti was in the 70s — the undisputed world champion of industrial design. Olivetti was world famous for TK; Jobs wanted Apple to take the crown.

There had been an explosion of design in the early 80s at the beginning of “the designer decade.” Design was especially hot in Europe, with groups like Italy’s Memphis Group of architects and designers earning accolades for their bold, colorful designs (memorably described as “a shotgun wedding between Bauhaus and Fisher-Price”). The Milan-based collective created a series of highly influential products in 1980s.

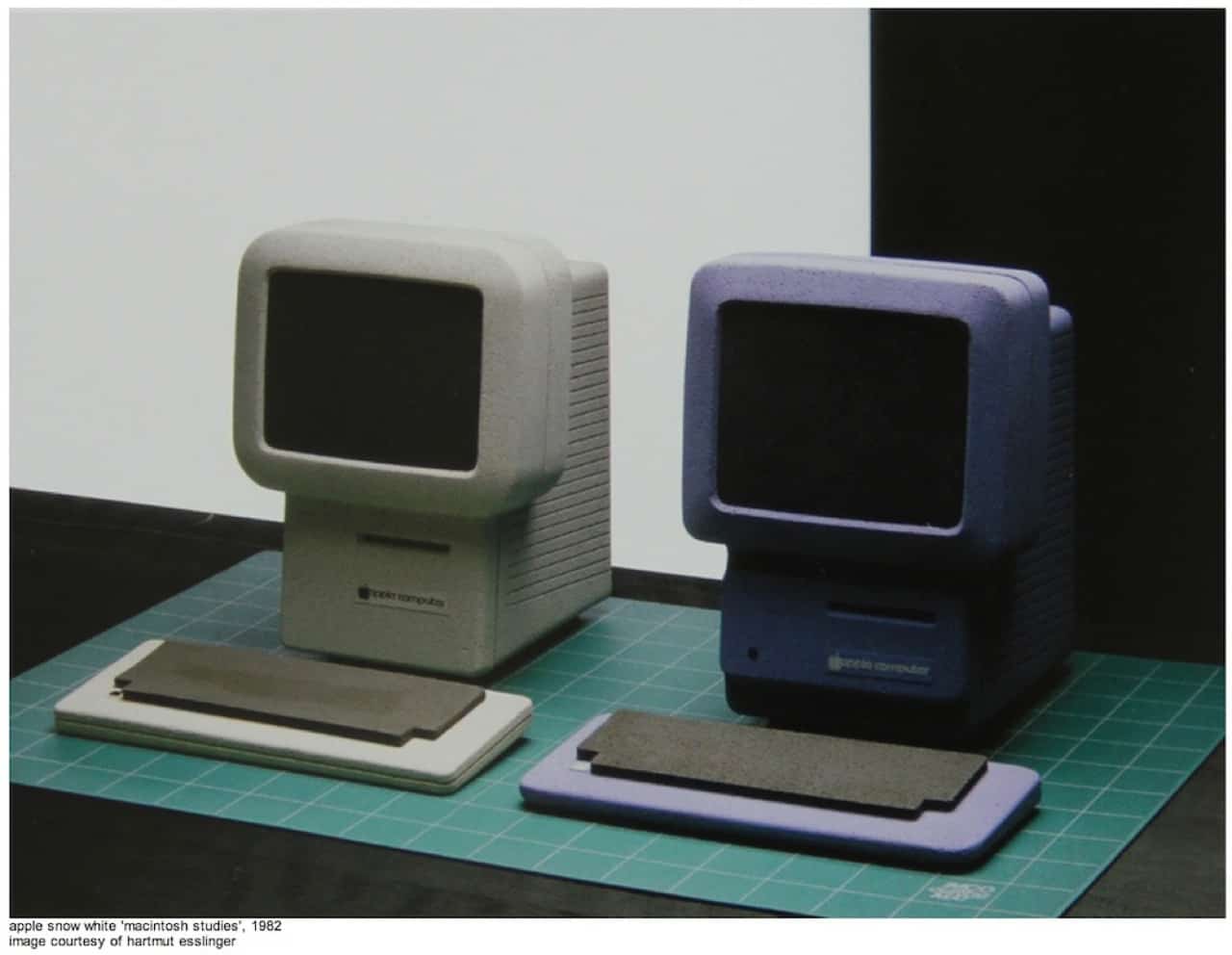

In March, 1982, two years before the Macintosh was unveiled, Jobs started looking around for a way to make Apple’s hardware as consistent as its software. Jobs decided Apple needed a “world class” industrial designer to craft a uniform design language for all the company’s products. He had Manock set up a design competition, in which potential candidates were asked to draft seven products, each named after a dwarf from Snow White. The name was inspired by the storybook Manock was reading to his young daughter. Jobs loved the idea: it conjured up images of products that were distinctive, friendly and with personality.

Apple’s different hardware groups drafted some detailed specs and descriptions for eight upcoming products (the seven dwarfs were joined by Flower from Bambi). Manock and a deputy went through a stack of design magazines looking for designers and design firms to enter the competition. After identifying TK, the product specs were shared with outside design groups from London and Germany. Within Apple, Manock also participated in the competition.

Almost from the start, the front-runner was a German industrial designer in his mid-thirties, Hartmut Esslinger. Like Jony, Esslinger had his own consultancy in Germany. He had a three-story studio in the picturesque, medieval village of Altensteig. He drove a cherry red BMW at insane speeds through the Bavarian forest. While he worked, he liked to play Deep Purple and the Rolling Stones at full volume. He didn’t want to hear the music, he wanted to feel it. Likewise, he wanted to feel design.

Like Jobs, Esslinger was a college dropout. He had gained notice designing TVs and other consumer electronics for Sony and Wega, a German consumer electronics company that Sony eventually bought. One of his TV designs for Wega was in bright green plastic, which the CEO of the company nicknamed frog. The name stuck, although the company now says the name is an acronym for Esslinger’s homeland: (f)ederal (r)epublic (o)f (g)ermany.

Esslinger and Jobs were both managerial. He didn’t do much of the hands-on work — a job delegated to his team of snot-hot designers — but he had great aesthetic taste, an eye for talent, and the gift of the gab. He was the firm’s salesman and director, and had developed an effective way of working with clients. He’d bond with executives and managers, absorbing the details of the brief. Back at the studio, he’d set his designers on several parallel paths simultaneously, and then take the best ideas and synthesize them into a solution that took the best ideas from the convergent paths. It was a smart and effective way to work. Jony would try something similar at Apple, with much less success.

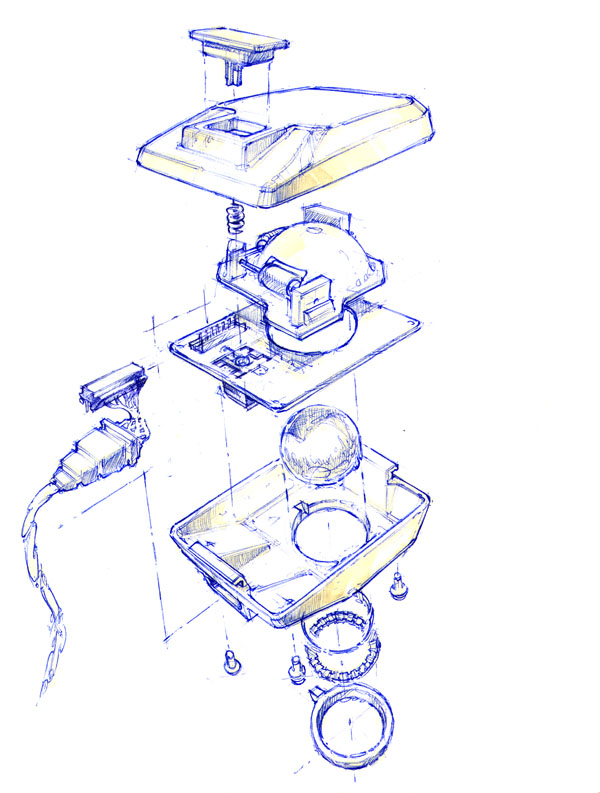

Esslinger was an early adopter of CAD and sophisticated model making. He made models that made Apple’s foam models look comically primitive. They were milled out of RenShape, a dense polyurethane foam shaped by a computer-controlled milling machine. After they were cut, they would be sanded and painted to show the final texture and color. They cost up to $50,000 apiece, a fortune in those days, and the best were almost indistinguishable from finished products. This kind of detailed model-making is a hallmark of Jony’s team at Apple, who took it to even further extremes.

As soon as he was invited to join the Snow White competition, Esslinger instead suggested a top-to-bottom strategic design review of everything the company was up to. Apple didn’t take him up on the ballsy offer.

At first, Jobs didn’t care for Esslinger’s sketches and initial ideas, which he judged too soft. He prefered the harder edges of the designs emerging from a London group. But in May 1982, Esslinger flew to Cupertino and the two hit it off. Esslinger was in many ways like Jobs. A natural entrepreneur, he was brash and opinionated. When the two first met, they bonded over a love of Braun and Mercedes. Jobs was particularly impressed that Esslinger had worked for Sony, a design-centric company that Jobs wanted Apple to emulate. Esslinger was a master at pitching his ideas and philosophy. In the world of contracting, it was his ability to sell ideas that was as important as raw creative talent.

Esslinger also knew how to work hard. His group labored through four major design phases, and after months of work put on an overwhelming show for Apple’s brass. The eight Snow White products included several next-generation computers, mice, printers and external floppy disk drives. While the other contenders in the competition made a handful of models, Esslinger’s group turned out 40 beautifully-finished models, two or three variations for each product. Jony too showed the same commitment in getting things right, no matter how many models he had to make. And whereas the other groups pitched designs in dark plastic with hard edges (like Sony’s stereo components from the eighties), Esslinger’s designs were lighter and more approachable. Simple but sophisticated, they were made from lightly textured, cream-colored plastic. Like Jony, Esslinger wanted to differentiate Apple from the masculine design of 80s electronics.

After a presentation in March 1983 in front of Apple’s top brass, Esslinger won the competition and Jobs was delighted. He felt Esslinger had the ability to make Apple’s design chops world class. The two agreed on a generous contract that would allow Esslinger to move his studio to California, working exclusively for Apple.

In 1983, Esslinger emigrated to California and set up his own studio, frogdesign, Inc. providing exclusive services to Apple for an unprecedented $100,000 a month, plus billable time and expenses. Billings would quickly add up to $2 million a year, far more than competing design firms were earning from their clients.

Esslinger located his new studio in Campbell, a suburb of San Jose in the heart of Silicon Valley. He bought a Intergraph CAD system, a CNC milling machine, and imported high-end chairs and drafting tables at great expense from Germany.

Now that he had a world class designer, Jobs unceremoniously told Manock and the other in-house designers that they would be working for Esslinger, who was essentially an outside contractor, albeit one with special status. Manock was killing himself getting the first Mac ready for Jobs, but Jobs told the hapless designers that they should consider themselves lucky to be in a position to learn from world-class talent. Most were more worried about their tenuous jobs (and indeed, the move more or less ended Manock’s career).

Looking back, Manock said he harbors no ill feelings. “In retrospect, my career experience at Apple was totally unique,” his aid. “When I left in 1984 I believed that never again would I get a CEO that appreciated design in the way that Steve did and was willing to pay for it. Steve demanded perfection, then trusted me to deliver it to him. For that I will be eternally grateful. Yes it was fun, frantic, and productive to be creating a product that was desired by a large number of people around the world.”

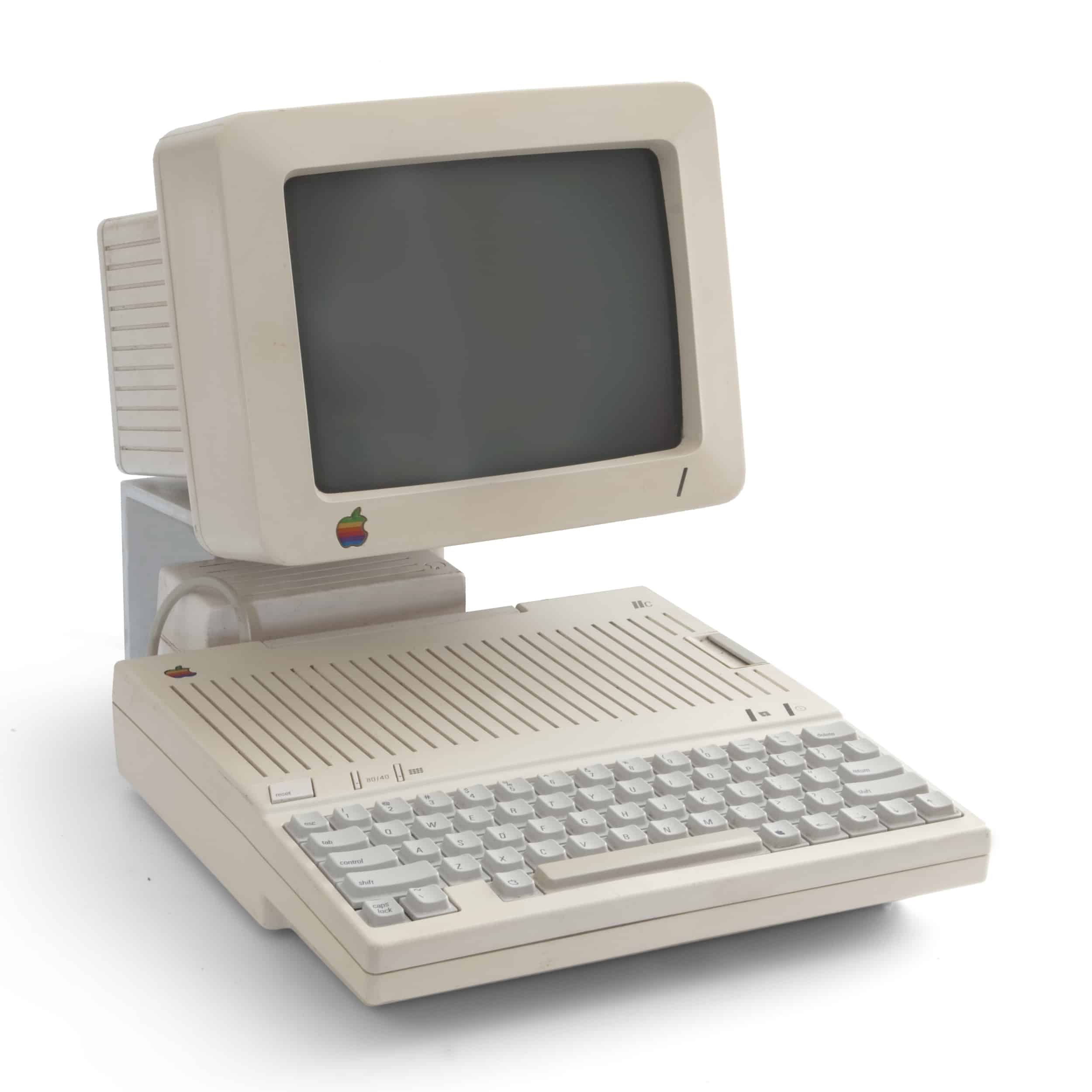

Courtesy Wikimeida Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apple_IIc_with_monitor.jpg

A key motif of Esslinger’s design were blocks of fine grooves that were etched into most of the computers’ flat surfaces. The blocks of grooves tended to break up the large flat planes, and made the cases look smaller than they were. It was a clever visual trick, well known in the natural world as a form of camouflage.

The grooves would be the key motif of the so-called Snow White design language, which dominated Apple’s design for nearly a decade. The grooves were 2mm thick and 2mm deep, spaced 10mm apart. Each block of grooves was set back 30mm from the front or back. The slots were too small to collect dust, but large enough to double as ventilation holes for the hot electronics inside. Snow White also defined chamfers, corner treatments and curves, lending Apple’s diverse product line a modern, unified look. Even before the Mac had been released, they made Apple’s best design efforts look clumsy and outdated. Snow White designs won allthe major industry awards, and was so widely copied, it became the de facto design language for the entire PC industry.

It was too late to redesign the Mac, which was already heading to tooling, so Frog’s first major product for Apple was the Apple IIc, the fourth in the line of Apple IIs and the first attempt at a portable computer (the “c” stood for “compact). More importantly, it was Apple’s first design-driven product (designed from the outside in, rather than the inside-out). The design was so compelling, the engineers bent over backwards to accommodate Esslinger’s designers, rather than fighting their ideas. It was a small but subtle shift; an early attempt to make Apple design-driven rather engineering-driven. The Apple IIc was named “Design of the Year” by Time Magazine and inducted into the permanent collection at the Whitney Museum of Art.

Snow White’s next big hit was the ImageWriter, a humble dot matrix printer. Dubbed the “poor man’s laser printer,” dot matrix printers were primitive noisy printers, low on the totem pole. Apple’s previous efforts were ugly, but the Snow White language could give even the humblest product a sense of style. The redesigned ImageWriter was a huge success, thanks to it’s slick, off-white shell, which gave it a space-age look. One reviewer described it as a “a cross between the lunar lander and paper shredder,” and people bought it as a piece of desktop sculpture. “People who knew nothing about design saw it and bought it because they liked the way it looked,” said Apple designer Daniel Peart. It was an early lesson in the power of good design.

Apple’s dot-matrix printer before Snow White styling:

After Snow White styling:

Post Jobs

Jobs was forced out of Apple in 1985 after losing a boardroom battle with John Sculley for control the company. But in his absence, the design wheels he’d set turning helped push Apple to to the top of the rapidly-growing PC industry. Apple’s revenue soared from $700 million in 1982 to $4 billion in 1986. Of course, the easy-to-use Mac software and the desktop publishing revolution were key too, but good design played a major role. In fact, the combination of killer design and killer software would be key to Apple’s later success.

But without Jobs, design at Apple eventually lost its place at the heart of the company. Without a champion, design became just another voice at the table — as detailed in the previous chapter – and eventually became subservient to marketing and engineering.

“Jobs was unique because he just had to develop great products. He was driven to do it. “ said Tony Guido, one of Esslinger’s designers. “That made him the best ally in the firm. He shared our dreams and understood what we were trying to do.” But when Jobs left, no one wanted to push the envelope any more. “Suddenly our role was to do the work and keep our heads down.”

Bob Brunner made an attempt to make the company more design-driven, with limited success. And when Jony took over the department, with the company losing market share and in financial crisis, things got worse.

Jobs Brings Focus

When Jobs returned, he brought focus to the company, and also to Jony’s design group.

Jony was ostensibly in charge of the design group, but their efforts weren’t unified. The group was in chaos, just like the rest of the company. The design department was fractured and rudderless. It was full of talented but willful designers, each working on their own projects with little or no coordination. There was no leadership from Jony, according to Doug Satzger, who was hired in 1996.

“Each designer had his own agenda, or her own design impulse, and there was no control [over their activities],” Satzger said. “One designer had an agenda over what a laptop should be; another had an agenda over what a printer should be. There was no consistency on what the next PowerMac tower should be. The design group was not set up so that designers could work collaboratively as a team. All the designers were independent and had their own strong design sense. It was like they were all working for different companies. And Jony Ive let this happen.”

Satzger said three designers were working on an update of the PowerMac, a powerful computer for professionals that came in a tower configuration. Each of the designs differed from the others. “There was no consistency,” said Satzger. “Danny [De Iuliis] had designed a perfect cube with wheels on it. It was pretty big. Danny Coster was working on a model that consisted of various blocks thrown together, while Thomas Meyeferhoffer’s design for the tower was all slurpy with lines all over — it was a monolithic piece of art. And the team was going ahead with not one of them but all of them.”

Brunner and Esslinger had both allowed designers to explore different design directions. Brunner in particular liked to treat the early design process almost as a competition. But he’d eventually choose the best ideas. Esslinger too would unify the best ideas into a single design direction. Jony had worked in this kind of environment for several years, but didn’t seem willing or able to provide a strong lead.

This is where Jobs stepped in. Jobs was busy shutting down unpromising projects and trimming back to just four products: his 2×2 matrix. Satzger remembers Jobs coming to the studio and telling the designers that Apple would be putting all its wood behind just four products. The first would be a desktop for consumers. “Steve said, ‘My daughter was going to college, and I’ve looked at everything out there and they’re all crap. There’s a real opportunity. Our target now is to build an Internet computer.’ He was envisioning the iMac. That was the new focus.”

++

Espresso Era

Moving to Cupertino

In September 1992, Jony accepted a full-time position at Apple and flew out to California with his wife Heather. He was 25 years old. The couple moved into a modest house on San Francisco’s Twin Peaks — the highest hill in the city. Their house enjoyed a stunning view of the city — all the way down Market Street to the skyscrapers downtown. “There is a fireplace in the sparsely appointed interior and a tiny television sitting atop an upscale stereo with a turntable, and virtually all the furniture is on wheels,” wrote reporter John Markoff, who visited Jony and his wife for a New York Times profile. “The room is lighted by a futuristic lamp, which appears to hang like a red orb, but there isn’t a personal computer in sight.” Jony bought an orange Saab convertible for the commute to Apple, about 35 miles away down the Peninsula in Cupertino.

In 1992, Apple was firing on all cylinders. It had grown from a tiny startup in Steve Jobs’ garage to one of the largest companies in the fast-growing PC industry. It was still several years before Apple would get into trouble. John Sculley was the CEO, having ousted Steve Jobs in a boardroom coup some seven years before. Jobs was struggling to make his followup companies — NeXT and Pixar — get off the ground. But at Apple, things couldn’t be rosier. The computer industry was exploding. Along with its rivals, Apple was riding the wave of the PC revolution. 1992 was a record year for revenues: Apple pulled in just over $7 billion, making it one of the biggest companies in the industry.

Having grown on the back of the desktop publishing revolution, Apple was expanding its product lines. The company was branching out from its core customer base in education and desktop publishing. It had introduced a super successful line of portables — the PowerBooks — and new, low-cost computers for ordinary consumers, the Performas.

Sculley was also getting a lot of attention for talking up a new line of innovative hyper-portable computers he called “Personal Digital Assistants,” a term he coined at a major speech at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Although it would be a couple of years before Sculley’s PDA would actually hit the market as the Newton MessagePad, the industrial design group was already hard at work on it.

Inside Bob Brunner’s Studio

Jony went to work in the industrial design group’s studio on Valley Green Drive in Cupertino, a short walk from Apple’s main campus on Infinite Loop.

At the time, the design studio was in Valley Green II, a large, low-slung building at 20730 Valley Green Drive that is surrounded by a few small trees and a big carpark. It’s on the other side of De Anza Drive, the main road through the center of Cupertino. Almost all of the buildings in the area are leased by Apple, making this part of Cupertino look like a company town. Apple’s first office, on Bandley Drive, is just around the corner.

Valley Green II, or VGII as it was known to Apple staffers, is about as nondescript a building as you can imagine: a featureless box in a business park full of other featureless boxes. Inside was a different story. Where the outside of the building was blank and featureless, the inside was filled with product prototypes and mockups. There were designer ‘toys’ everywhere: spendy bikes, TK and TK. There was an expensive CNC milling machine, and later an early 3D printer for making prototypes. On the walls were big glossy prints of some of the group’s best work.

“The ID studio at Apple was a cool workspace, with open cubes,” recalled Rick English, a photographer who did a lot of work with Apple in the 80s and 90s. In 1997, English published a book about the design group with Paul Kunkel, a freelance writer, called Apple Design.

“It was pretty fun visually,” English recalled. “Typical ID space. Toys everywhere. Lots of mountain bikes.” English worked with a lot of other design studios in the Valley, but Apple’s stood out. “They were having a lot more fun,” said English. “It fostered this really creative, take-a-risk atmosphere, which I didn’t see at other firms.”

Brunner’s recruitment to Apple:

Designer Robert Brunner, former Director of Industrial Design at Apple

The design studio was the brainchild of Robert Brunner. It was Apple’s first internal design studio. Most design work had been outsourced to outside design agencies. And the choices Brunner made in setting it up were auspicious; they’d have wide-ranging impact on Apple later on after Steve Jobs returned.

Before Brunner, Apple had contracted most of its design to Frogdesign, a full-service design consultancy run by the hotshot German designer Helmut Esslinger. However, in the late 1980s, Frog was starting to get expensive. Its billings were more than $2 million a year, twice what it would cost to use other outside design firms and much more expensive than running a small in-house design team. But Apple was stuck in a contract that Jobs had struck up with Esslinger in the early 80s, and couldn’t get out without paying a huge penalty.

By 1987, Apple was starting to think seriously about building an internal design team, but without Jobs, the engineers had no idea where to start. Because design had been contracted to Frogdesign, there were no designers on staff. And because Apple had been working exclusively with the company, there were no relationships with other design firms. Management at first tried to find a superstar designer to replace Esslinger, thinking the firm needed someone with a world-class reputation.

In early 1988, they embarked on a worldwide tour of the world’s most famous design studios on a quest to find a superstar designer, a fruitless search that at one point bordered on farce. They travelled to Europe and Asia, interviewing design firms like Porsche Studio. They visited top designers in Tokyo, London and Berlin. But none were quite right. In Italy, they visited Mario Bellini — the so-called “crown prince of italian design,” who rudely dismissed them. Not to waste the trip, they set up a meeting with Italian designer Giorgetto Giugiaro, the world famous “Car Designer of the Century” who is synonymous with Italian style. Giugiaro designed more cars than anyone else in the twentieth century. Hired by Fiat at age 17, he was responsible for scores of gorgeous Bugattis and BMWs, Maseratis and Ferraris.

When Apple executives went to visit him in his giant, factory-like, ultra-secure Italdesign studio near Turin, he was sketching with one hand, talking on the phone with another, while continually issuing orders to his many minions. The executives were so impressed, they offered “Il Maestro” a $1 million contract to design concepts for just four products, which they hoped to use as models for a whole line of products. But Giugiaro was used to designing cars — from the outside in. He would make loose, impressionistic sketches of cars, which his model makers would use to make 1:1 clay models. Often, the finished models would differ from the sketches, sometimes quite a lot. Over several months, the Apple engineers discovered that the Italdesign studio’s model makers did most of the actual design; Giugiaro was more of a muse. His sketches were more inspiration for the finished designs. It was the opposite of the way things were done in California. Giugiaro applied the same methods to the Apple commission: His model makers designed the computer casings using clay — just as they would high-end Italian sports cars — with little regard to the internal components, and the models didn’t translate to manufacturable products.

At one point, the Apple team also went to see hotshot Swiss-born German designer Luigi Colani, one of Jony’s design heroes, who was famous for crazy, “biodynamic” designs of cars, motorcycles and consumer goods. Colani gave them the idea of a split ergonomic keyboard based on the idea that men like to grab women’s backsides. After delivering a lecture at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, he was asked about the future of keyboards and launched into a long diatribe comparing keyboards to women’s bottoms. Since men like to grab women’s rears, the keyboard should be split up the middle to accommodate different hand sizes, he said. To illustrate his loony theory, he drew a woman’s bottom with keys on it and handed it to one of Apple’s staff, who was almost too embarrassed to take it. Back at Apple HQ, the story spread, and the staffer’s colleagues bought a female mannequin and stuck keys to it, replacing his regular keyboard. The stunt drew outrage from Apple’s female staff, but the idea remained. Apple’s computers soon had split ergonomic keyboards.

Meanwhile, Apple was making vast sums of money riding the desktop publishing revolution. Thanks to the Mac’s graphical user interface, great layout software and cheap laser printers, Apple was selling boatloads of machines to newspapers, magazines and book publishers.

At the end of 1988, Apple had three factories working 24 hours a day, seven days a week, processing more than 40 million pounds of plastic. It had a budget of $200 million for R&D, but one executive joked at Macworld that it had nothing to spend it on. There were 20 products in various stages of development, but no concepts. Some of Apple’s various departments — peripherals, portables, desktops and so on — had started working with outside firms like Lunar and IDEO, but there was no coordination between groups. Apple had reverted to the pre-Snow White days. Once again, the company needed a unified design language to give the products cohesion.

During the past couple of years, Apple had been working quite a lot with Bob Brunner at Lunar. The first projects were bluesky projects, designed mostly as tests — like the one Brunner would later give to Jony at Tangerine. It was all under the table. Apple couldn’t formally work with another design firm because of the exclusive Frog contract. Apple’s accounting department wouldn’t pay anyone for design work unless the invoice included Frog’s name and vendor number. But Lunar called it “product design” instead, which implied engineering rather than design, and no one in accounting had heard of Lunar so they got paid.

Apple sent less and less work to Frog, the billings dropped precipitously and eventually stopped paying the firm its retainer. Meanwhile Esslinger was secretly working with Jobs at NeXT, his new startup — in violation of the contract with Apple. In TK, the two companies agreed to nullify their contract.

Apple realized that it had its superstar designer right under its nose: Bob Brunner. Brunner had been doing stellar work, and the company had been delighted with everything he’d done. Brunner was attending design meetings and making suggestions for maturing Snow White and transitioning Apple to a new unified design language. Apple started trying to recruit Brunner, twice offering him the job of design director, but he wasn’t interested because Apple had no design organization. He felt the job would be a dead end: he’d end up a middle manager overseeing outside designers like himself.

“I didn’t want to work at company that wasn’t designing its own stuff,” said Brunner. “I didn’t want to manage people doing the creative work, I wanted to do the creative work,” he said. “Of all the companies in the world, this company could have a really amazing in-house design team… it should have a really amazing studio, it has great products. A great brand. Great history.”

By 1989, Apple was getting desperate. Apple tried again, this time asking Brunner what would it take? Brunner said he wanted to build a great team. Turn Apple into a world-class design company. But Brunner didn’t want to build a big design organization. “There are great corporate design divisions in companies — Nike, Samsung — but they are massive, multi-armed.”

Instead, Brunner wanted to recreate a small design consultancy like his company Lunar, but within Apple. “The original premise was we have a small, really tight studio,” he said. “We would run it like a small consulting studio, but inside the company. Small, effective, nimble, highly talented, great culture. And that’s what we set out to do. It was because really, I didn’t know any other way. It wasn’t a flash of brilliance: that was the only thing I knew how to do.”

Plus, there weren’t any good models to emulate. No other company in Silicon Valley had anything like an internal design group. “We weren’t really emulating anybody,” Brunner said. “The culture out here is very fast moving, very entrepreneurial, very idea oriented. That kind of creative studio in companies works here. It may not work in other company cultures.”

Apple agreed and Brunner joined the company as head of industrial design in January 1990. He was 32 years old. “I thought I’d made a huge mistake. I got there and it was, here’s your cubicle, in a sea of engineers. I thought Oh God, what have I done?”

Setting up studio:

Despite his intentions to hire a dream team of designers, it was about 18 months before Brunner settled in and started hiring in earnest. In 1991, he started really building the team, but first he had to find a cool place for them to work. “We set about creating a cool studio inside the company,” Brunner said. “That was essential to recruiting talent. I can’t have people working in cubicle hell. They won’t do it. I have to have an open studio with high ceilings and cool shit going on. That’s just really important. It’s important for the quality of the work. It’s important for getting people to do it.”

Brunner found an underutilized building that Apple was leasing on Valley Green Drive, a leafy road not far from the main campus. The building was VG II — right across from VG 6. Half of the building was available. It was a big open space with 25 to 30-foot ceilings. In the other half of the building was Apple’s Creative Services group, who are known as Apple’s “In-House Design Consultants” and are called on to produce brochures, manuals, branding materials, in-store posters and displays, exhibits, and video promos. Crucially, the building was not directly under the noses of Apple’s meddlesome executives. “I liked that it was off the beaten path,” Brunner said.

Brunner worked with Studios Architecture, a San Francisco design firm, to transform the interior into a cool design studio. [TK MORE ON STUDIOS ARCHITECTURE]. Apple had standardized on Herman Miller office furniture — the company credited with inventing the cubicle — but Brunner didn’t assemble it into cubes. Instead, the desks were arranged in unusual formations around the space. “We used the taller structures as spines running around the studio and the work spaces running off it,” said Brunner. “The corporate planning people didn’t get it. They said you can’t do that, but that’s what we did, put it together in different ways. It totally freaked them out. It was great, a lot of fun. We just made it less oppressive.”

Brunner had a CAD workstation installed for creating 3D models of designs; a CNC milling machine to turn the CAD models into foam ones; and a paint shop for testing different colors.

TK — IS THIS STANDARD DESIGN SHOP SETUP: CAD, CNC, COLOR?

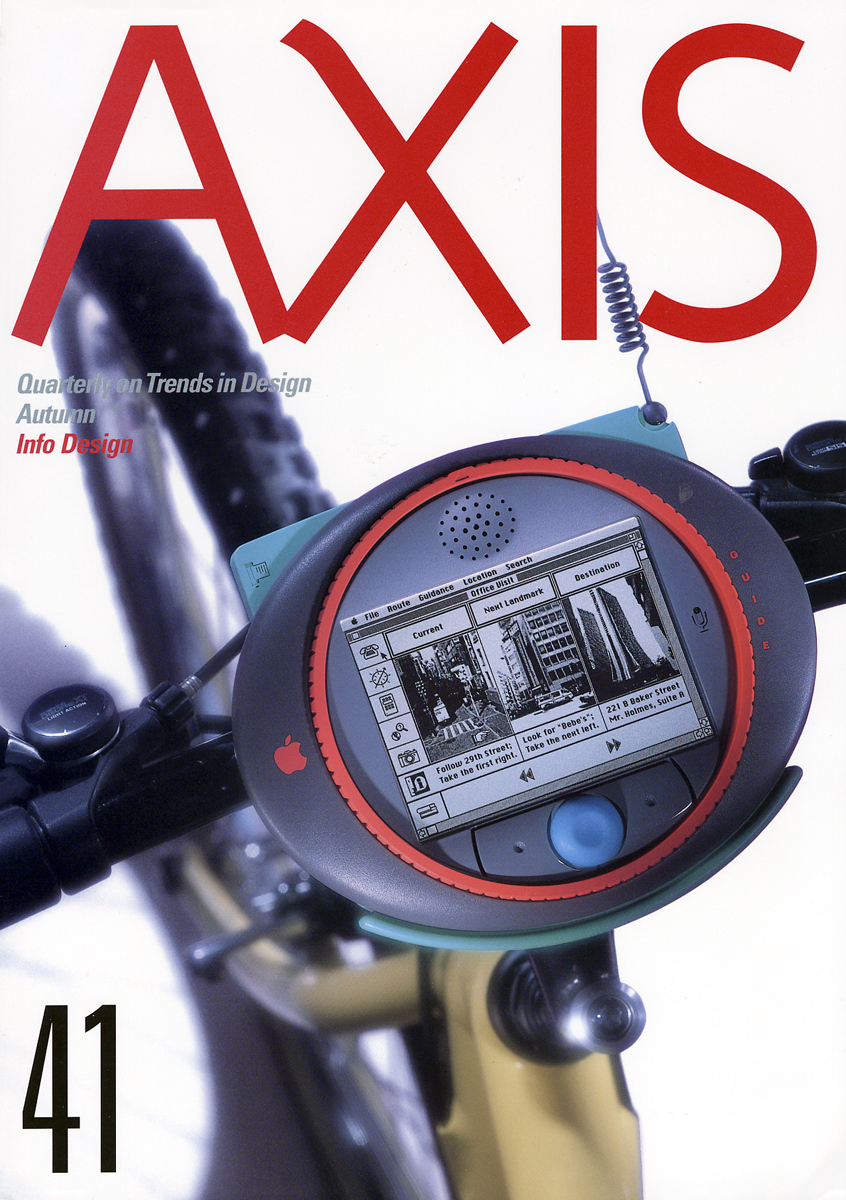

Brunner started recruiting in earnest. But it was tough going attracting talent. Apple had no reputation for doing its own design: it had outsourced it to Frog. Talented, ambitious designers would rather go to firms like IDEO, also in the Bay Area. To help with recruiting, Brunner took a leaf from Tangerine’s book. He created mockups of fantastical Apple products and ran big glossy photos of them on the back of I.D. Magazine, the international design bible. One was a gigantic bicycle navigation computer that showed maps and local landmarks on a black-and-white screen. Another was a chunky wristwatch ‘computer’ the size of a cantaloupe. “They were concepts, not real products,” said Brunner. “They started to get attention. It was totally recruiting. No other reason. They were sketchy, information appliance models. A little bit tongue in cheek, but it served its purpose.”

When Jony arrived, he joined a group of eight talented designers, some of whom would continue to work with Jony for decades and contribute to Apple’s smash-hit successes. When Jony joined in 1992, Brunner’s team consisted of Tim Parsey, Daniele De Iuliis, Lawrence Lam, Jay Meschter, Larry Barbera, Cal Seid and Bart Andre.

[TK CUT THESE MINI BIOS? Meschter is a talented industrial designer who worked at Apple between 1990 and 1997 and went on to be the creative force behind Nike’s Flywire technology as part of the shoe company’s highly regarded Design Kitchen team. At Apple, Meschter worked on nearly all of the major projects of the time.

Larry Barbera was one of the product design leaders at the industrial design team and worked at Apple between 1987 and December 1995. His tenure coincided with the work of Apple’s earliest mid-80s designs, from Hartmut Esslinger’s Frog Design (including Snow White) and the Robert Brunner era. Barbera would end up leaving the company along with Brunner. Barbera received a BS degree in Industrial Design from the Ohio State University

Tim Parsey is from the U.K, graduating from the Central Saint Martin’s School of Art and Design in 1982 with a degree in Industrial Design. Recruited from IDEO in 1991, Parsey was quickly designated as the unofficial administrative leader of the group. He worked for the IDg group until 1996. Two of his designs at Apple, the Stylewriter II printer and the QuickTake digital camera are part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Daniele De Iuliis (pronounced day-YOU-lease) was perhaps the most talented of the group. Born in Bristol, UK, of Italian descent, De Iuliis graduated in 1983 from the Central Saint Martins School of Art and Design in London with a BA in industrial design engineering. Brunner hired him in 1991 from the San Francisco office of design group ID2 (where Jony’s friend Grinyer had earlier worked). Brunner specifically wanted designers with experience in consulting. “After experiencing the inertia that exists inside Apple, Bob realized that by hiring former consultants he could operate with the speed and efficiency of a freelance group,” said Parsey. “As a former consultant, Bob knew that we would think and act like consultants.”

Fellow designer Barbera was impressed with his personality right away: “Danny, in particular, gave off that weird light that other designers tend to notice. I took one look him and figured that our work was gonna get a lot better, fast.”

De Iuliis was able to give his designs strong personality, a skill that served him well later on. One of his early projects was the Macintosh Color Classic, an update to the original Mac that exuded a ton of personality and was avidly collected by fans for years. He would later work on the MacBook Pro and the iPhones 4 and 5. He was granted a patent for the iPod shuffle (fourth generation) along with other designers. He is named in more than 560 patents inventions, which are vast and varied in scope. They include innovations in 3D cameras, multitouch displays, location tracking, RFID transponders, nitriding stainless steel, magsafe charging mechanisms, the iPod, improved speaker enclosures, and on and on.

De Iuliis was an early champion of CAD within the group. “Designing with CAD doesn’t change our ideas,” he said. “It helps us realize them in ways 2-D drawings cannot.”

Later in his career, De Iuliis would receive top design awards for his work. TK AWARDS. De Iuliis and Jony lived close together in San Francisco and commuted together for more than 20 years.

In 1992, the group recruited Bartley K. Andre, an intern in Apple’s Personal Intelligent Electronics, or PIE group (no joke). Better known as Bart, Andre graduated from the University of California at Long Beach in 1991. Doing some freelance consultant after graduating, Andre was building products that were noticed by Brunner. Andre was the lead designer on several notable products, including a line of leather and metal-bound PowerBook laptop concepts designed with Jony.

Over the years, Andre would become one of the top five patent-holders in the United States on a year-to-year basis. Thanks to his last name, he is listed on all of Apple’s major patents in the title. “United States Patent Application Andre et. al.” By 2013, Bart had more patents to his name than any other Apple designer including Jony. In 2009, he received 92 patents and 114 in 2010, a record number of patents for an Apple designer. Most of the patent awards were for innovations on the phone, tablet, and laptop lines.

Andre has worked on everything at IDg, from circuit modules to the RFID systems. He received the Red Dot award, along with the team, for his work several times. Among the most important awards in the industry, the Red Dot was given based on his work for the iBook, the iMac 4G, the wireless mouse, the wireless keyboard, and the Titanium PowerBook G4.

Andre is also credited with the design of Apple’s 035 design prototype of the first iPad, according to information released during the Apple-Samsung trial in 2012.

When Jony joined the design team, they were excited about him joining them. “Bob knew the effect that a strong new designer would have on the group,” said Meschter. “When Daniele De Iuliis and Tim Parsey first arrived, our whole approach to design changed. But when Jonathan came on board… the group really took off.”

In the summer of 1994, Daniel J. Coster joined the team. A “tall, goofy, super-talented” New Zealander, Coster is one of a small number of top world designers from Down Under.

Coster earned an industrial design degree from the Wellington Polytechnic school in New Zealand in 1986. Following graduation, Coster ran his own consultancy in Wellington for a year before spending four years working in Australia for the KWA Design Group, also in New Zealand. At KWA, Coster gained product experience designing furniture and sports equipment. He would later say his work at KWA influenced his decision about joining Apple. “Having worked on a range of consumer and lifestyle options, I want to inject some of that spirit into Apple’s next generation computers.”

During a visit to the United States in 1993, Coster showed his portfolio to studios in New York and California and began working for Apple. In June 1994, Coster took a three-month position as a contract worker at Apple and worked on colors and finishes for the Newton portable. He designed various towers and gained notice for being the lead designer of the Bondi-Blue iMac. Later, he worked on the iBook and TK G4 during Apple’s renaissance as well as most of the other major products of the 2000s, including the iPhone and the iPad.

By 2004, Coster and the rest of the Apple team were receiving constant praise and awards for their innovative product output. Together, they won the Design of the Decade Gold Award from the DA&D, the industry’s top honors, as well as the British Design and Art Direction Association.

Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs describes Coster as the “top deputy” to Jony in the last few years. In total, Coster has received nearly 600 patents working for Apple during the last 20 years.

In 2012, Coster was inducted into his alma mater’s design Hall of Fame. An induction in the Hall is made to those school graduates “who have made an outstanding contribution to New Zealand’s economy, reputation and national identity through art and design.” Previous inductees include Sir Richard Taylor of Weta Workshop (the Lord of the Rings movies), sculptor Len Lye, and fashion designer Kate Sylvester. Massey CoCA students and alumni greeted his induction with great affection. On Twitter, one CoCA alum cried, “Bless you Danny you changed my life!”

Coster was also prominently involved in the recent Apple-Samsung trial. He testified on the following topics of his expertise: design and development of Apple’s iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch products.

Group Structure

To run the group like an outside consultancy within Apple, Brunner set up a loose management structure, which largely persists today. The main focus was a “pool” of designers, who worked together on whatever project the group was facing. “There was the studio, the pool of talent,” Brunner explained. “We’d work on multiple projects, and move from project to project, pretty much the way he [Jony] does it today.”

Brunner also made about half a dozen of the designers “product line leaders.” There was a product line leader for each of Apple’s major product groups: CPUs, printers, monitors and so on. The PLLs acted as the primary contacts out to the company. “Each designer was liaison to each group,” Brunner said. “The product groups felt there was a contact within the design group. They managed the communication and the different needs of each group. I didn’t know any better. I ran it like the Lunar studio. There’d be discussion of a project. We’d design it, make it and ship it.”

However, as Apple grew and thrived, riding the DTP revolution and the exploding market for PCs, the group found itself churning design after design on shorter and shorter schedules. When Brunner first started at Apple, the product development cycle was 18 months or more. “It was crazy generous,” Brunner said. “You had an amazing amount of time to make something work. And within a matter of years, that shrunk to 9 to 12 months, and sometimes even 6 months if there was a quick turn on something. All of a sudden, what got compressed was our thinking time. It still took just as long to implement something, but the time to explore, to test and to play with, just went away.”

At this point, Brunner formulated his offline “parallel design investigations,” which allowed the group to explore forward-looking concepts without the pressure of a production deadline. “We had an enormous number of products in the pipeline: two lines of desktops, monitors, printers, mobile products. Way too many. It was an enormous amount of work. More than we could handle.”

In addition, Apple’s internal culture heavily favored the engineers within the product groups. The design process was engineering-driven. In the early days of Frogdesign, the engineering groups had bent over backwards to help implement the design team’s ambitions, but now the power had shifted. The different design groups gave their products in development to Brunner’s design group, who were expected to merely “skin” them.

To shift the power from engineering to design, Brunner started thinking strategically. “We began to realize we need to own this thing more,” Brunner said. “We began to do more longer term thinking, longer term studies around things like design language, how future technologies are implemented, what does mobility mean?” The idea was to get ahead of the engineering groups and start to make Apple more of a design-driven company, rather an marketing or engineering one. “We wanted to get ahead of them, so we’d have more ammunition to bring to the process,” Brunner said.

One of these longer-term studies was the Juggernaut project with Tangerine. Brunner used several other outside resources for his investigations, especially Lunar and IDEO, a practice that continues to this day, although Jony and Steve Jobs never admitted it publicly. It also allowed the overworked design team to work with talented designers not on the Apple payroll. “Sometimes we wanted to hire specific designers to act as part of the team, to use them as freelance talent,” Brunner said.

++

Brunner was good at getting attention for the group, which inevitably led to design awards. Every month, Brunner continued to run ads on the rear cover of I.D. magazine. Instead of bluesky concepts, Brunner ran a big glossy photo of one of his designer’s prototypes, just to give them attention and make them feel good.

A lot of the photography was contracted out to Beverley Harper and Rick English. For English, the Apple design group turned into one of his biggest clients. English spent a lot of time at the studio photographing foam models, the rough, early prototypes that followed them, and the final detailed models. English also shot the finished products themselves; a ritual that signalled the end of a long, sometimes painful project. “Typically, by the time a product was ready for a photo shoot, the designer had been working on it for at least six months or a year,” he said. “The photo shoot was in a sense what made the product real. If the photos appeared in BusinessWeek, for example, they could be seen by ten or fifteen million people.”

It was expensive. English said he was billing the company at least $250,000 a year. Some of the work that the team had done was displayed as big photos on the wall of the ID space. “In the space on Valley Green, we had some Rick English shots and Beverley Harper shots: some of the work we were doing in detail,” recalled one designer. “And we had those on the walls and that was it. There wasn’t much.”

Brunner also liked exploring parallel design concepts, setting up projects almost like competitions. For every product that could have got made at Apple, there were two to ten design directions that they explored. “It was almost like a competition, which Bob encouraged,” said English. “Then, when one of those designs was selected it became that designer’s baby all the way till completion.”

“And I photographed all the designs. The mindset was that there was going to be a historical archive of all the things they worked on. In that group, they absolutely believed that their work had such importance. They were just then breaking away from the gray-box look of computers. Of course, not all the stuff they designed was ever produced.”

The design group continues to document everything it does. Sally Grisedale, the former manager of Apple’s Advanced Technology Group, which worked closely with the design group, said the systematic documentation set Apple apart.

“It’s all written down. It has to be. There are so many moving parts,” she said. “Even when I was there, all the processes were worked out. That’s why [Apple] was such a perfect company to work for, because they had booklets on how they do it, and they helped you, when building the software or the hardware, it had to be really systematic. So it was a very rude awakening for me to go a different company like Excite or Yahoo because they had none of that! Nothing written down. Like, process? Are you kidding? Just ship it and get it out there!”

In hindsight, Brunner’s choices — the studio’s separation from the product groups, its loose structure, collaborative workflow and consultancy mindset — all of these turned out to be fortuitous. One if the reasons Apple’s design team has remained so effective is because it retains Brunner’s original structure. It’s a small, tight, cohesive group of extremely talented designers who all work on design challenges together, just like the designers did at Lunar, Tangerine, and other small agencies.

+++

The Design Team

[TK PARSEY WAS NUMBER 2, BUT PASSED OVER WHEN BRUNNER QUIT] Jony soon began to emerge as second in command to Brunner. Not only did he provide brilliant ideas and superb design taste, he was helping to build the design team that he would later head up and go on to create a string of groundbreaking products.

Jony would be integral in the recruitment of the next group of designers. Within a couple of years in the mid-90s, Jony hired most of the team that would go on to make the iMac, the iPod and the iPhone. This group included Christopher Stringer, Richard Howarth, Thomas Meyerhoffer, Duncan Robert Kerr, and Doug Satzger.

Christopher Stringer was born in Australia in 1965 and was raised in the North of England [TK CHECK]. He attended North Staffordshire Polytechnic in Stoke-on-Trent and graduated from London’s Royal College of Art in 1986. Stringer joined IDEO in 1992 where he helped develop Dell’s design language and won an ID Design Review award for an innovative light switch.

In 1995, he was recruited by Jony as a Senior Industrial Designer, working on the early PowerBooks and tower computers. In his 17 years at the company he has been involved in all the major releases, peripherals, and in even smaller projects, like the designing of the product packaging. Stringer worked on the original iPhone and almost all of Apple’s mobile products. TK patents.

Over the years, he’s often been spotted at Apple launch events talking side-by-side with Jony, giving the impression they are close friends. They are both from Staffordshire and studied in the north of England. He was the first designer to give testimony at the Apple-Samsung trial. “Stringer looked every inch the designer with his shoulder-length hair, salt-and-pepper beard, wearing an off-white suit with a narrow black tie,” reported Reuters.

Richard Paul Howarth was born in Lukasa, Zambia, and graduated from Ravensbourne college in London in 1993. At college, he won an apprenticeship with Sony in Japan for a minidisk Walkman prototype called the Telephatik Fish. After graduation, Howarth went to the Bay Area to work at IDEO for a few years before joining the Apple IDg group in 1996. He worked on the PowerBook line with Christopher Stringer and over the years became one the group’s main designers. He was the lead designer of the original iPhone, and a major contributor to the iPod Touch and iPad.

Another designer from the UK, Duncan Kerr is a current Apple industrial designer with nearly 15 years’ experience building the company’s most important products. Like several others, Kerr was recruited from IDEO, where he met several of his future Apple colleagues. At IDEO, Kerr worked on many projects in interaction design, often developing innovative working prototypes.

As one of the team’s technical and engineering leads, Kerr has great influence in the development and investigations of new products and technologies. He helped pioneer the multi-touch technology that led to the iPhone and iPad. He is often one of the first contacts between the ID and Product Design groups. Kerr graduated from the Imperial College London school with a degree in Mechanical Engineering in 1985 and followed it with a two-year degree program at the Royal College of Art in Industrial Design Engineering. While at Apple, he has received numerous patent awards. They include recognition for his work on the iPad, iPod flash, iPod nano, iPhone, the latest earphones and various technical innovations involving components like proximity detectors, display modules, and magnetic connectors.

Doug Satzger worked at Apple between 1996 and 2008 in the Industrial Design Group. An Ohio native, his interest in materials and knowledge of manufacturing processes made him the group’s design lead for color, materials and finishes, working on the first iMac to the latest iPhone, iPods, iPad and MacBooks.

Satzger attended the University of Cincinnati and graduated in 1985. He started his career at IDEO as an industrial design lead, before designing TVs at Thomson Consumer Electronics.

Satzger’s has been named in many patents, mostly in packaging, electronic devices, displays, cursor controls, and connectors.

Satzger was heavily involved in the development of the colorful line of iMac G3s, whose success and popularity, most of it based on Satzger’s whimsical color choices, led to Apple’s renaissance. He also came up with the iPod’s iconic earbud cables’ white color.

After Apple, Satzger joined HP/Palm as the senior director of industrial design. Satzger is currently the vice president of the Mobile and Communications Group and general manager of Industrial Design at Intel.

TK — Russell-Clarke?

De Iuliis spelled out Jony’s recruitment philosophy and expectations. Engineering and computer skills were a plus, but not absolutely necessary. The group would rather hire a talented car designer than a mediocre computer one. “We are looking for personality, overwhelming talent and the ability to work in a small group,” said De Iuliis. “We also want to be impressed with a designer to the point of intimidation.”

The other key member of the group at that time was Calvin Seid, a native of Portland, Oregon, who graduated from San Jose State University in 1983 and worked for design firms in Oregon and Silicon Valley after graduation. He joined the Apple IDg in 1993 to design and manage CPU projects. His first major design for Apple was the Quadra 605, code-named ELB for Extremely Low Budget. He knocked it out of the park. His design would be considered a classic and expanded to several more systems. Seid received more than 80 patents. He died unexpectedly on April 6, 2007, of coronary artery disease at the age of 46. He was popular and his death upset the team greatly.

The design team was distinctly international, but largely white and male. Except of Sied, who was of Filipino descent, the team were all young white guys. There were also no women until the 2000s, when Jony hired Jody Akana [TK MAYBE Kristi Bauerly and Irene Chan-Jones. They remain the only [TK TWO or THREE?] two women on the team.

“Jony’s had that core of people around since then, they’ve been commuting up and down highway 280 together for 20 years now, between San Francisco and Cupertino,” said Sally Grisedale. “They’re tight. They’re family. Many started as single men and then they had families and now all live in the same neighborhood.”

The iDG was a great place to work, but nobody ever quit. The lack of turnover was a challenge for the group. It was difficult to bring in fresh talent. It worried Jony: “Though we don’t want people to leave the group, the lack of movement makes it difficult to bring in fresh talent,” he said. “We need new people at regular intervals to prevent ourselves from stagnating. But this can only happen if other people are willing to leave.”

[TK MOVE Over the years, the core members of the group would be Jony, Stringer, and Howarth.]

The Espresso Aesthetic

Now that the team was in place, they started working on a new design language for Apple’s products. The older Snow White language was getting long in the tooth, and besides, it was hard to adapt it to Apple’s growing range of products. Snow White had been invented for computers, not printers, handhelds, speakers and portable CD players.

The team developed a new language called “Espresso,” a Euro-style aesthetic characterized by swooping organic shapes, bulges and an adventurous use of colored and textured plastics. It was less a design language than a loose set of guidelines and best practices: an aesthetic. There were no hard and fast rules. But like pornography, the designers knew it when they saw it.

One of the first Espresso products was the Macintosh Color Classic, an update of Steve Jobs’ original Mac by De Iuliis. Like the Mac, it was an all-in-one machine, but De Iuliis lengthened it’s face, made the vents look like gills, gave it a higher forehead and made the floppy slot even more mouth-like. It was more bulbous and curvy than the original, with a distinct personality. Users went nuts and turned it into a highly-collectable machine.

The most distinctive “Espresso” touch were a pair of small round legs at the front that looked like the feet of a baby elephant. The “fat feet” became one of the most distinctive elements of the Espresso look. They tilted the computers upward by six degrees and made them look “like an eager pet staring up adoringly at its owner,” said Don Norman.

The feet came about through a stupid lucky break. “Came from a fuck up,” said Norman. “Early pizza box machine was about to go into production, [we] focused so much on making it slim and flat we forgot about the floppy slot on the front. Not enough room to insert a disk with a keyboard in front of the machine. So we added a pair of feet at the front that tilted the box up. Had the unexpected effect of giving the machine a lot of personality… [and it] became a design feature that was featured prominently for five years.” Indeed, it was a design language that influenced later generation of smash-hit products after Jobs returned. The iMac has its origins in Espresso.

The Espresso name, interestingly, has two possible origins. The official story from Apple is that it was inspired by the minimalist design of the modern European coffee pots the group used while working. The unofficial, and more likely story, comes from Don Norman: “The name was a derogatory term applied to the new design team who had just installed a fancy espresso coffee machine in the studio. One old-time engineer said it was a sign of the ‘yuppification’ of Apple, and started calling them ‘espresso.’ The funny thing is, the designers didn’t get it and adopted the term for their new design language.”

++

When jony started at apple, there was Brunner and tim parsey and under tim was jony and other designers. And parsey is design language written up document of all the specifications of how you design something. You know ‘the vents have to be this way, the colors have to be this way’, the radius on things iOS only this, ‘ that’s design language, that’s how you define a language and that’s very typical in designing in. Apple’s initial design language snow white, all those things were based on color, corner radii,\ part to part flat size, gapping between all the vents, how you could use and you can introduce new things to them, it was hard , and you broke that, that’s where steve comes in, or if it was jony and team, and the design quality is the material ands the quality that you build into the product.

Tim parsey was espresso, it wasn’t a real design language, I interviewed about 4-5 months after bob left. When i interviewed, parsey was still there but on his way out. Lawrence law was still there but on his way out. Pretty much everyone was there other than the core team of Danny D, Bart and Jony, and Cal. And the rest of the team were hired within a two year period — stringer, howarth, meyerhoffer, satzger, duncan kerr,. That was the core team for years. And then rohrback, then whang, then shin, then rico. Then Peter Russell-Clarke.

Satzger on motivation — designing for Steve, and for themselves.

Plus how previous design era was rule based, whereas Jony’s approach was looser, freezer